The Gem City is home to several innovative and inventive minds, but perhaps none are as recognizable as The Wright Brothers and their invention of flight. So this time we’ll be taking a look at how this invention was made, the claims that dispute the narrative we all know and what being the birthplace of flight means for Dayton.

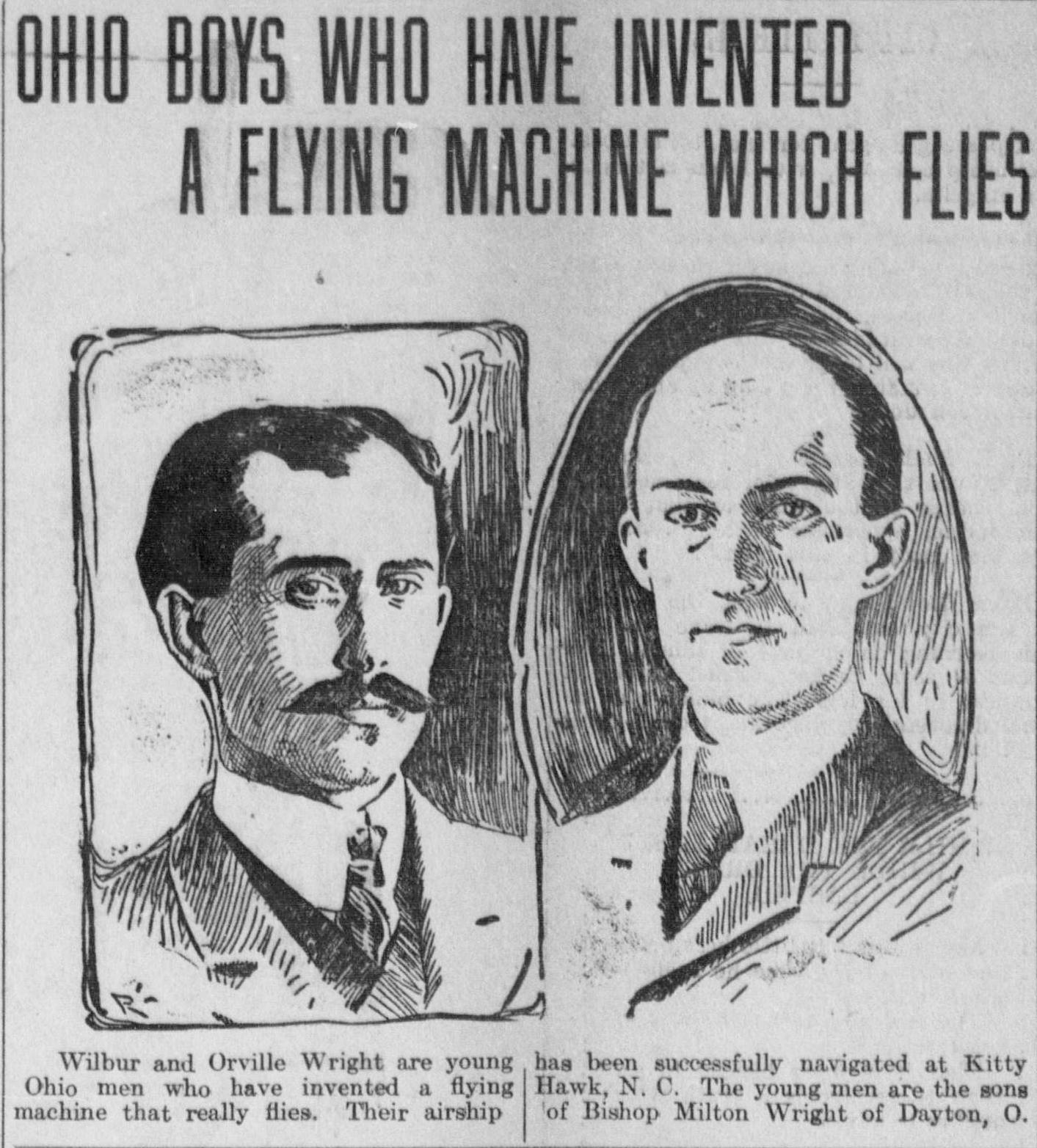

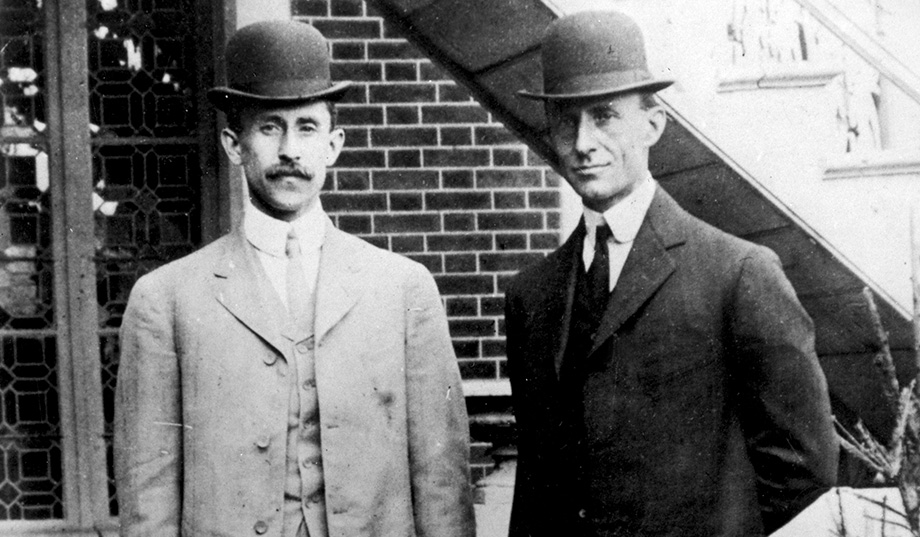

Wilbur Wright was born in 1867 in Millville, Indiana. Orville was born four years later in Dayton in 1871. They had five additional siblings, although twins Otis and Ida died in infancy.

Milton Wright, their father, was a clergy member and made several trips as a member of the Church of the United Brethren in Christ. In 1878, he gave Wilbur and Orville a toy helicopter made of paper, bamboo and cork with a rubber band used to twirl its rotor. The two played with it until it broke and later built their own replacement. In interviews, they have cited the toy as sparking their interest in flying.

The family moved permanently to Dayton in 1884, and the brothers faced academic troubles. Wilbur couldn’t earn his high school diploma due to the move, and couldn’t play sports due to a hockey injury.

In this time he became distant and withdrawn. He spent his time caring for his mother, who was ill with tuberculosis, and read constantly. He was upset over his lack of ambition during this time.

Orville dropped out of high school in 1889, and started his own printing business. Wilbur joined and together created their own publication, West Side News. The issues listed Orville as publisher and Wilbur as editor.

In April 1890 they converted the paper to a daily, The Evening Item, but it lasted only four months. After this they focused on commercial printing jobs.

One of their clients was Orville’s friend and classmate, Paul Laurence Dunbar, a Dayton resident who rose to international acclaim as a groundbreaking African-American poet and writer. For a brief period the brothers printed the Dayton Tattler, a weekly newspaper that Dunbar edited.

Following their foray in the printing industry, they joined in on a booming bicycle market, opening their own bike shop in 1892, the Wright Cycle Exchange (later called the Wright Cycle Company). They produced their own brand of bicycles and used the money made from the business to focus on their growing interest in aviation.

Following their foray in the printing industry, they joined in on a booming bicycle market, opening their own bike shop in 1892, the Wright Cycle Exchange (later called the Wright Cycle Company). They produced their own brand of bicycles and used the money made from the business to focus on their growing interest in aviation.

One event in particular peaked the Wrights interest in flight. In 1896, German experimenter Otto Lilienthal lost control of one of his gliders and was killed by the landing. He was one of the earliest pioneers of flight, writing several articles and photographs of his glides that influenced the brothers.

The Wrights cited this as the point when they seriously started their interest in flight.

Wilbur said: “Lilienthal was without question the greatest of the precursors, and the world owes to him a great debt.”

The Wrights knew that a successful airplane would need wings to generate lift, a propulsion system that was powerful enough to keep it moving through the air and a system to control the plane in the air. This was the component Lilienthal didn’t have.

Wilber’s solution to this problem was inspired by how birds would change course and control their path. They would change the angle of the ends of their wings to make their bodies roll right or left.

They decided that this banking or leaning into a turn would be a good way for a flying machine to maintain control. This would also help them to recover their control when wind would tilt the machine to one side. One problem was figuring out how to make man made wings have the same effect.

They then discovered wing-warping after Wilbur idly twisted a long inner-tube box at the bicycle shop. When wings would be twisted, one end of the wings produced more lift than the other. This unequal lift made the wings tilt, or bank. The end with more tilt rose, and the other end dropped, causing a turn in the direction of the lower end.

The brothers first tested this technique with a large model box glider, which were controlled by four cords attached to it. The brothers then started testing manned gliders in 1900 at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The location was closer to the mid-Atlantic coast with regular breezes and soft landing surfaces, while still being remotely close to Dayton. It also provided them privacy from reporters.

The brothers first tested this technique with a large model box glider, which were controlled by four cords attached to it. The brothers then started testing manned gliders in 1900 at Kitty Hawk, North Carolina. The location was closer to the mid-Atlantic coast with regular breezes and soft landing surfaces, while still being remotely close to Dayton. It also provided them privacy from reporters.

The brothers spent the next two years perfecting the glider, adding more improvements to the design. The major breakthrough came from the two finding the purpose of the movable vertical rudder. It helped aim the aircraft correctly during turns and helped level it off when facing sharp turns or wind disturbances. Turns were done using roll control by the wing-warping.

These factors all combined to result in success when the Wrights achieved true control on their turns on Oct. 8, 1902. Their longest glide lasted 26 seconds and covered 622.5 feet. This success prompted them to make a powered flying machine.

They then applied for a patent for a flying machine on March 23, 1903.

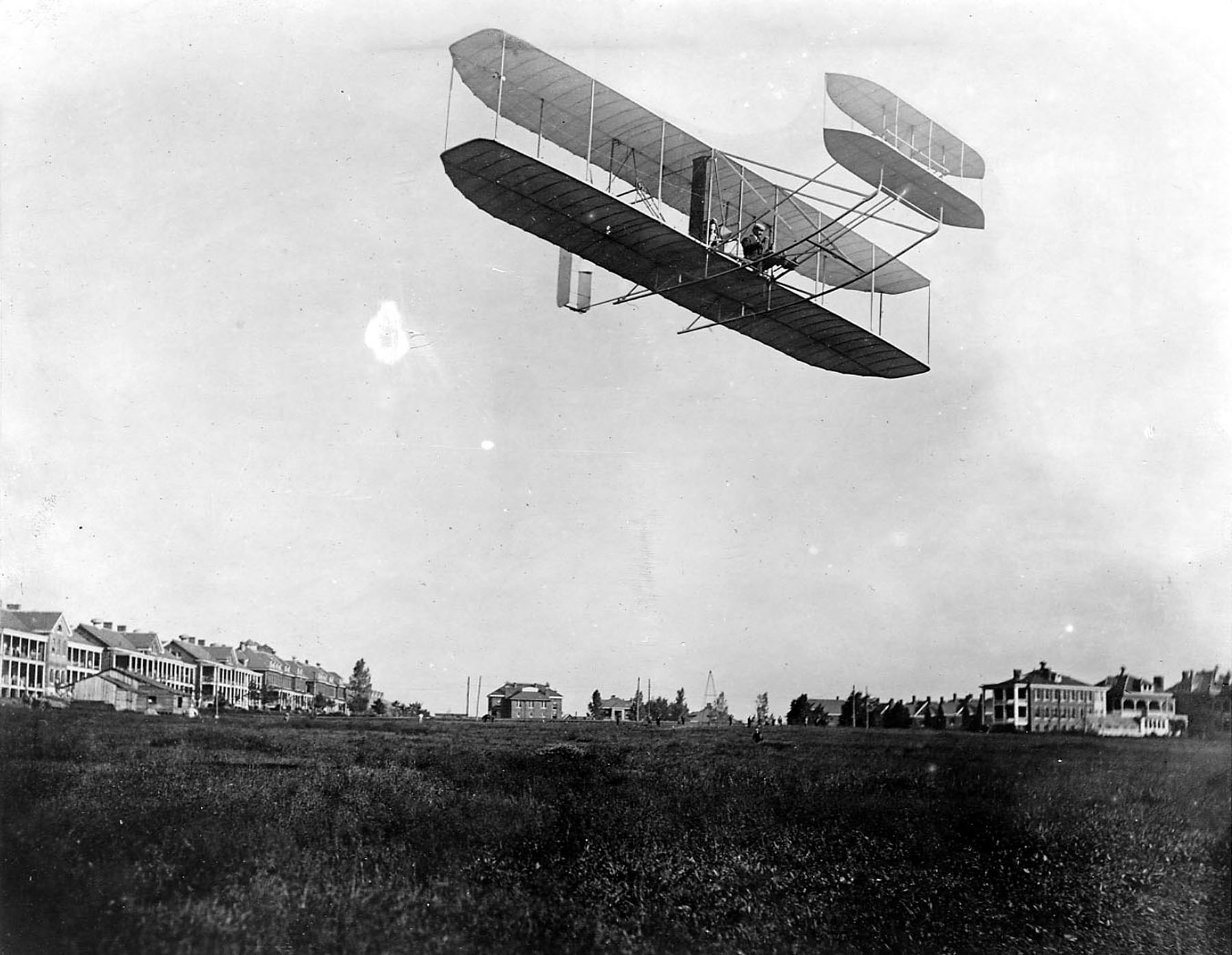

Later on that year the Wrights built the first powered model, the Wright Flyer I. Using spruce, their preferred wood due to the lightness of it, and wooden propellers designed by them and two prototype gasoline powered propellers, the brothers put a focus on the plane being lightweight and efficient.

The next roadblock was the engine, as the Wrights wanted it to be light and not weigh down the plane. They accomplished this by having their shop mechanic, Charlie Taylor, build an engine block cast from aluminum, a rare procedure for the time.

The Flyer cost less than a thousand dollars, and had a wingspan of 40.3 feet, weighed 605 pounds and had a 12 horsepower 180 pound engine.

On Dec. 17, 1903 in Kill Devil Hills North Carolina, Orville made the first successful flight, covering 120 feet through the air in 12 seconds. Wilbur flew 175 feet in 12 seconds on his first attempt, followed by Orville’s second effort of 200 feet in 15 seconds. During the fourth and final flight of the day, Wilbur flew 852 feet over the sand in 59 seconds.

This was the first time in history a heavier-than-air machine had demonstrated powered and sustained flight under the complete control of the pilot.

In 1904, they ran more tests with more updated Wright Flyer models at the Huffman Plain near Dayton. Their efforts were troubled at first, with several failed attempts. Then on Aug. 13, Wilbur made an unassisted takeoff that exceeded their Kitty Hawk effort with a flight of 1,300 feet.

They then started using a weight-powered catapult to make takeoffs easier. This led to Wilbur flying the first complete circle in history by a manned powered machine, covering 4,080 feet in about 90 seconds. By the end of 1904, the Wrights accumulated 50 minutes in the air in 105 flights.

By mid 1905, great strides were being made in their inventions, with longer flights covering more distance, and the media began to notice. Fearing that their invention would be copied, they stopped flying until they could get the machine protected by patents. This led to much doubt from countries overseas that the brothers were capable of creating flight.

They didn’t fly in 1906 and 1907, as they spent those years in attempts to get military contracts and investors to fund their product and eventually sell them. Eventually they were able to persuade the U.S. Army and a French syndicate to buy in to their product, providing there was a live demonstration.

This meant the brothers were divided, as Wilber sailed to France and Orville demonstrated in the states.

The Wrights faced a heavy amount of skepticism from the French press, who questioned if they even conducted a successful flight. These doubts were put to rest on Aug. 8, 1908, when Wilbur conducted a series of flights that wowed spectators.

He performed banking turns and figure eights, feats that were unheard of in the French aeronautical community. He took several passengers during these flights as well.

Georges Besançon, an editor of aviation magazine L’Aérophile, wrote that the flights “have completely dissipated all doubts. Not one of the former detractors of the Wrights dare question, today, the previous experiments of the men who were truly the first to fly …”

Wilbur’s journey to France was a massive success. Orville’s demonstration to the U.S. Army at Fort Myer, Virginia would prove to be disastrous. It started well, as he conducted the first hour long flight on Sept. 9 1908, lasting 62 minutes.

However, tragedy struck on Sept. 17, when Army lieutenant Thomas Selfridge rode as a passenger during a flight. A few minutes in at an altitude of 100 feet, a propeller split and shattered, sending the Flyer out of control toward the ground.

Selfridge suffered a fractured skull and died later that evening. Orville suffered fractures in his hip bone, a broken left leg and four broken ribs. He was hospitalized for seven weeks, but was undeterred in his mission.

His response to a friend who asked him if he lost his nerve due to the accident: “Nerve? Oh, do you mean will I be afraid to fly again? The only thing I’m afraid of is that I can’t get well soon enough to finish those tests next year.”

After licking his wounds Orville and the Wrights’ sister Katherine joined Wilbur in France. They conducted several more flights there before giving addition demonstrations in Italy.

They returned to the states in Spring 1909, and were bestowed awards by President Taft. They then were showered with a two day homecoming celebration in Dayton.

Their success would continue in July, when the duo completed proving flights for the U.S. Army, meeting the requirements of a two seater being able to fly with a passenger for an hour at an average speed of 40 miles per hour and land undamaged. They sold the airplane to the Army’s Aeronautical Division for $30,000.

The brothers were bonafide celebrities, as they were known the world over. Approximately a million spectators watched Wilbur fly a circle around the Statue of Liberty.

Controversy started in 1909, when the brothers sued fellow inventor Glenn Curtiss, who begun to sell planes that used ailerons, a part the Wrights took credit for using.

Controversy started in 1909, when the brothers sued fellow inventor Glenn Curtiss, who begun to sell planes that used ailerons, a part the Wrights took credit for using.

The bitter legal battle lasted several years, along with the brothers suing foreign aviators who flew at U.S. events. Their manufacturing companies sued as well, and it got to a point where Curtiss’ people suggested that “if someone jumped in the air and waved his arms, the Wrights would sue.”

The lawsuits went on for several years, long after Wilbur’s death in 1912. They damaged the brothers’ public reputation, as well as their own progress.

By 1910, the Wrights’ aircraft designs were inferior to those made by other firms in Europe. U.S. aviation was in such a state that no acceptable American designed aircrafts were available to use when they entered World War I.

The legal battles ended in 1917, when the U.S. government created a patent pool called the Manufacturer’s Aircraft Association between the two major patent holders, the Wright Company and the Curtiss Company. This ended the feud that previously blocked the building of new airplanes for the war effort.

Both brothers ceased flying during the legal battles, and Wilbur died in 1912 following a battle with typhoid fever.

Orville sold the company in 1915 and served on several boards and committees relating to aviation, including the National Advisory Committee for Aeronautics (NACA), and Aeronautical Chamber of Commerce (ACCA). He was at NACA for 28 years.

He passed away in 1948, 35 years after his brother. Both brothers were buried in the family plot in Woodland Cemetery, and cemented their spot as the creators of sustained flight.

Henry Wolski

Executive Editor