Disclaimer: This is not a review of the film. Instead this is an exploration on the themes of the film and why I feel they are important in our modern time.

“The way of life can be free and beautiful. But we have lost the way,” says Charlie Chaplin, famed silent actor in perhaps one of the greatest speeches ever put to celluloid. Chaplin was addressing an English speaking audience in late 1940; at this time most of Central Europe, including Czechoslovakia, Poland, Denmark, Norway, Belgium, Netherlands and large portions of France were under Axis control.

It’s clear that in Chaplin’s “The Great Dictator” he was speaking to a much more fractured, more disturbed world. The extent of the atrocities committed by the Third Reich weren’t at that point public knowledge but there was a general consensus that to be a Jew in Europe was a precarious prospect.

As ships crossed the Atlantic carrying Jewish refugees while Germany herded them like cattle into ghettos and then into camps, some refugees even fled east, creating a small community in China, until the Japanese invaded and forced them into a one square mile long district in Shanghai that was fraught with disease and overcrowding, Chaplin made his film, wherein he played a Jewish barber and a political despot much akin to that of Germany’s own despot, Adolf Hitler.

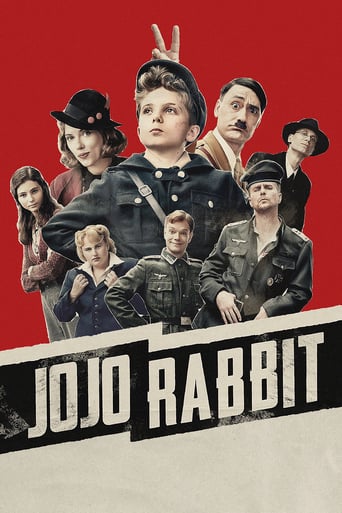

Taika Waititi’s film “Jojo Rabbit,” released on Oct. 18 and now playing at The Neon, a theater on 5th Street, a block away from the Oregon District, owes a great deal to Chaplin’s film, not just for having similar doppelganger Hitlers but also for creating films about finding empathy in a world caught up in the engines of hate.

We are still at a transitory period, being in the present and therefore cannot determine with any kind of accuracy how we will view our world in the time to come or our politics, for that matter. But there has undoubtedly been an effect over the past couple of years on our culture.

Our modern age has seen a growth in the visibility of various far-right, white-supremacist groups much like Richard Spencer’s National Policy Institute, a white supremacist think tank headquarted outside of Wasignhton D.C. and Mike Enoch’s “The Right Stuff,” an alt-right media network and podcast “The Daily Shoah,” the latter being a play on Comedy Central’s late-night talk show, formerly hosted by Jon Stewart, himself a Jew by heritage and the Hebrew term for the Holocaust, Shoah.

Related Articles:

In fact, according to an NPR article written last February, hate groups have seen a 30% rise in the U.S., this according to the Southern Poverty Law Center, a civil rights organization that tracks hate groups. And there’s no denying the effect that hateful rhetoric has taken on young impressionable boys.

The El Paso shooter wrote, before attacking a Walmart, killing 20 and injuring dozens more, that his intent was “a response to the Hispanic invasion of Texas,” something that seems to echo the rhetoric of a political leader who refers to Mexican immigrants as “rapists,” insinuating that they’re bringing drugs and crime along with them.

The same could be said for Dylann Roof, whose views against minorities led him to shoot up an African-American church in Charleston, South Carolina.

“I did what I thought would make the biggest wave,” wrote Roof, in a prison cell, weeks after the shooting, “and now the fate of our race is in the hands of my brothers who continue to live freely.”

In Charlottesville, at the Unite the Right Rally, a 20-year-old from Toledo, Ohio (my hometown) ran his car through a crowd of people, killing one and injuring others. The driver was a young male. An ex-schoolmate said that the driver would draw swastikas on his notebooks and talk about his love of Hitler as early as middle-school.

Then, in May of this year, the Washingtonian ran a story written by an anonymous author stating that their son had joined the alt-right and had adopted sexist views and had become a moderator on an alt-right subreddit. Though it’s not clear if this is a true story, it illustrates effectively how a young, impressionable mind might adopt extremist views, views that, much like “Jojo Rabbit’s” titular character give the individual a place to belong.

“I’m not saying I’m gonna be able to change every single person with this film,” said Waititi of the film in a promotional interview. “But I do feel like it’s an important film for our time right now because I feel like we can never stop dealing with what happened during World War II. Some people might say, ‘Yeah, but that’s so many years ago,’ it’s not that many years ago.”

Waititi has experience helming movies about loners and outsiders. His career was jump-started with his “Napoleon Dynamite” ala New Zealand “Eagle Vs. Shark,” a movie about two socially awkward loners who deal with past trauma and fall in love. The same can be said for “Hunt for the Wilderpeople,” a movie about a juvenile delinquent who is forced on an adventure with his cantankerous foster father after his loving foster mother dies. Or, the endlessly hilarious, “What We Do in the Shadows,” a mockumentary about vampires living in modern-day New Zealand that is packed with more heart and much more enjoyable than it should ever be.

Waititi’s career has flourished as of late, too, having helmed one of the better Marvel films, placing a disgraced, out of place Thor with a sad, insulated Hulk. The results, much like Waititi’s other films was joyous and heartfelt, injecting genuine pathos into a comedy about superheroes fighting on a planet in which a day-glo covered Jeff Goldblum is the leader.

It’s with this deft detail and empathy that Waititi makes Jojo more than just a hateful boy but instead a young man trying to find his place in a world that is offering up false and telling him it’s truth. Jojo becomes a Nazi because it allows him a place to fit in, buying into the propaganda and inventing new propaganda with his close friend Yorki, the two buying into their invented truths about Jewish people, no matter how ridiculous.

The redemption then comes in the second half of the film wherein Jojo is forced to question his ideals and come to terms with the truth underneath all of the propaganda. I won’t spoil it but I will say that it is very much a rather realistic depiction of learned empathy through proximity and understanding.

I wish that I could bottle the joy that I feel when I watch a Waititi film, and save that joy for the coldest, grayest day of winter, because on that day, that bottle would genuinely work. Yes, he makes Hitler funny. Yes, he makes a young Nazi kid funny. Yes, he makes Nazis funny (not that that hasn’t been done before). But what makes “Jojo Rabbit” great and important is that it doesn’t treat hate like an alien ideal that can’t be understood.

Instead, Waititi, who himself plays Hitler, presents Jojo as a sad, frightened boy who just wants to be accepted and who sees Hitler much in the same way that teenagers saw the Beatles in the late ‘60s. With Hitler as Jojo’s imaginary friend, he projects an ideal friendship for a confused boy.

Matt Johnson, 34-year-old director of the 2013 film, “The Dirties,” a somewhat comical film about two school shooters that effectively displays how, without focusing on the aftermath, and instead on the joy of having a confidant, once suggested in an interview that he wanted to make the main culprit genuinely charismatic and fun to be around, like a good friend, because he thought that making the people who do vile things as something other than human doesn’t allow for a way to solve the problem, it only puts a very small band-aid over a gushing wound.

Jojo does that effectively, using the story of a disillusioned boy (among others) looking for a place to belong and tries to root out the source of the hate and why they might have gone down the path they did. It gets inside the fervent fanboy nature of hate and finds the root of the ailment, healing it with understanding and comedy, rather than outright alienation and aversion to the offenders.

Upon “The Great Dictator’s” release, because of Chaplin’s choice to play a Jewish barber and because he had spent the time and effort to take down Hitler, it was spread around that Chaplin himself was Jewish. Though Judaism wasn’t seen as badly here in the States at this time as it was in Berlin, Chaplin never made any attempt to correct these reports about his supposed religious beliefs.

In his biography, amongst the fear United Artists (the production company backing the film) had of producing a satire of Hitler, as it might be seen as too controversial or might not play in England, Chaplin later remarked that he was determined to go ahead with making the film anyways.

“For Hitler must be laughed at,” said Chaplin in his autobiography.

It’s been said that darkness can not be rooted out by darkness, only love can do that, so says Martin Luther King Jr. Somehow, for some reason it seems we at times have forgotten that fact and “Jojo Rabbit” tries instead to shed love on hate, in the hopes that it might drive it away. With the shear will of kindness and understanding that Waititi employs on the majority of his films, I would say he’s probably up to the task, if anybody is.

Richard Foltz

Executive Editor