It’s Women’s History Month, and Staff Writer Henry Wolski is taking a look at some of the lesser known stories of important women throughout history for the next couple weeks. Expect to find tales of bravery, strength, revenge and intrigue in this series.

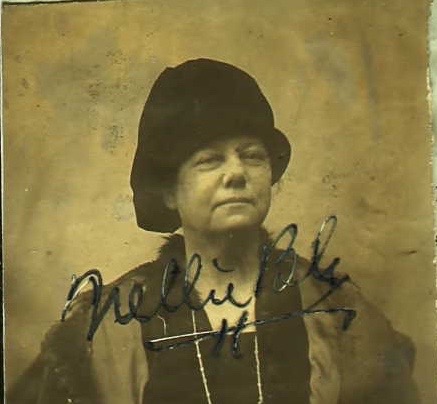

Elizabeth Cochran, known by her pen name Nellie Bly, is an important figure in the history of journalism. Her courage in tackling dangerous and hostile stories in the late 19th-century formed the beginnings of the practice of investigative journalism.

Cochran was born on May 5, 1864 and grew up on her father’s mill in Pennsylvania, located in modern day Pittsburgh.

Cochran became a columnist at the Pittsburgh Dispatch after writing a strongly worded letter to the publication in response to “What Girls Are Good For,” an article that proposed that women are necessary only for birthing children and keeping house, impressing the editor. Ultimately, she coined her pen name based on a character in the Stephen Foster song, “Nelly Bly.”

In her time writing for the Dispatch during the early 1880s, she covered topics such as divorce law reform, the lives of women working in the factory system and reporting on the lives and customs of the Mexican people for half a year.

During the excursion to Mexico, she protested the imprisonment of a local journalist for criticizing the Mexican government, a dictatorship under Porfirio Díaz. When Mexican authorities learned of Bly’s report, they threatened her with arrest, prompting her to flee the country. When home, she accused Díaz of being a tyrannical czar suppressing the Mexican people and controlling the press.

Despite this, citizens complained about her coverage and she was reassigned to covering fashion, society and gardening which frustrated her.

Later, she moved to New York and marched into the office of Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World. After demanding a story and promising she could deliver, she was sent to infiltrate the Women’s Lunatic Asylum on Blackwell Island (present-day Roosevelt Island), which was getting several complaints about the treatment of its inmates, with no guidance on how to get in or out.

Bly practiced looking insane in front of a mirror by staying up late in the night. She then checked herself into a working-class boarding house, hoping to frighten the other boarders so much that they would kick her out.

She pretended she was from Cuba and ranted she was searching for “missing trunks,” in addition to yelling at other boarders. This worked, and she was sent to Blackwell Asylum.

She was there for 10 days before lawyers from The World negotiated to get her out. Her findings were posted in several articles and later published as a book, “Ten Days in a Madhouse.”

In it, she comments on the quality of the food served in mess halls. Her tea “tasted as if it had been made in copper.” Bread was overcooked to the extreme, a crispy black brick, and some even had insects on it. Food such as soup was cold and featured spoiled meat.

During her first few days at the asylum, she was forced to take an ice-cold bath in dirty water, sharing only two towels with 45 other inmates.

“My teeth chattered and my limbs were goose-fleshed and blue with cold,” she wrote. “Suddenly I got, one after the other, three buckets of water over my head — ice cold water, too — into my eyes, my ears, my nose and my mouth. I think I experienced the sensation of a drowning person as they dragged me, gasping, shivering and quaking, from the tub. For once I did look insane.”

Bly talked to as many inmates she could, and found that many were sane. Some were immigrants that couldn’t speak English, and others were impoverished women that thought they were being moved to a poorhouse, not a looney bin.

Abuse was rampant at the institution. Women who dared to cry or speak out were beaten, choked, kicked, drowned and some were given internal injuries. The doctors would deny these beatings, telling patients that it was a fabrication of their unstable minds, and they would get punished again for telling.

Nurses drugged inmates with “so much morphine and chloral that the patients are made crazy,” Bly wrote. “The attendants seemed to find amusement and pleasure in exciting the violent patients to do their worst.”

Bly puts it all together in this paragraph:

“Take a perfectly sane and healthy woman, shut her up and make her sit from 6 a.m. to 8 p.m. on straight-back benches, do not allow her to talk or move during these hours . . . give her bad food and harsh treatment, and see how long it will take to make her insane. Two months would make her a mental and physical wreck,” Bly wrote.

The first part of her article was published on Oct. 9, 1887, and was an instant hit, making waves in the public and helped jump-start investigations into the asylum. Unfortunately, administrators were wise and transferred the women that spoke to Bly out and cleaned up the facilities before inspections could be made.

However, a grand jury awarded the asylum $1 million towards repairs, believing the words that Bly had written.

With that, Bly was famous and encouraged the “stunt girl” movement, full of female reporters, all using pen names, infiltrating establishments like hospitals, factories, court systems and many other industries to uncover the corruption within. Names like Annie Laurie, Eva Gay and Nora Marks are just a few that followed in Bly’s footsteps.

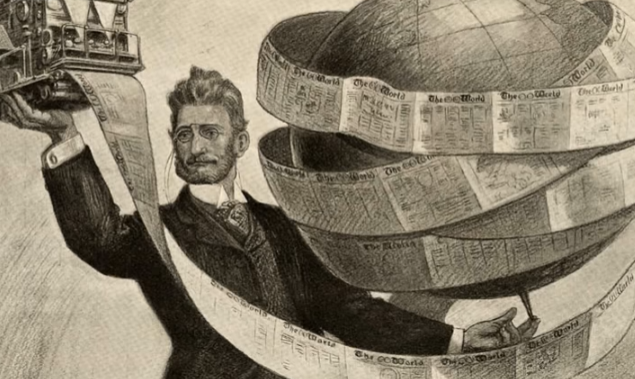

Bly’s work continued as she sought a new challenge: becoming the first person to actually make the journey of fictional character Phileas Fogg in Jules Verne’s novel “Around the World in Eighty Days.”

From Nov. 14, 1889 to Jan. 25 1890, Bly began her 40,070-kilometer trek across the globe traveling by steamship and railroad setting the first record at 72 days. She held the record for a few months, until George Francis Train, a mogul in the textile industry, and the potential inspiration for Verne’s novel, finished a 67 day run on May 24, 1890.

In 1895, Bly married millionaire manufacturer Robert Seaman and stepped away from journalism to help manage his enterprise, the Iron Clad Manufacturing Co., receiving a few patents in the process for milk can and stacking garbage can designs. The business ultimately went bankrupt following Seanman’s death in 1904 due to negligence and an embezzlement scandal from a factory worker.

In her later years, Bly returned to journalism, notably covering the Eastern Front in Europe during World War I, where she was one of the first foreigners, as well as the first woman to visit the war zone between Serbia and Austria.

In addition, she reported on the Women’s Suffrage Parade of 1913, organized by the National American Woman Suffrage Association (NAWSA). This was the first suffragist parade in Washington, D.C., as well as the first large organized march on Washington for political purposes.

Bly passed away at St. Mark’s Hospital in New York City in 1922 from pneumonia. She was 57.

She remains a pioneer in the field of journalism, being one of the very first reporters to infiltrate corrupt institutions and report from the inside. She was inducted in the National Women’s Hall of Fame in 1998. Additionally, the amount of accolades, acknowledgments and portrayals in media of her are too vast to list here.

Bly remains an integral part of the history of journalism and laid the groundwork for every reporter that has stepped into harm’s way in the interest of exposing corruption.

Henry Wolski

Staff Writer