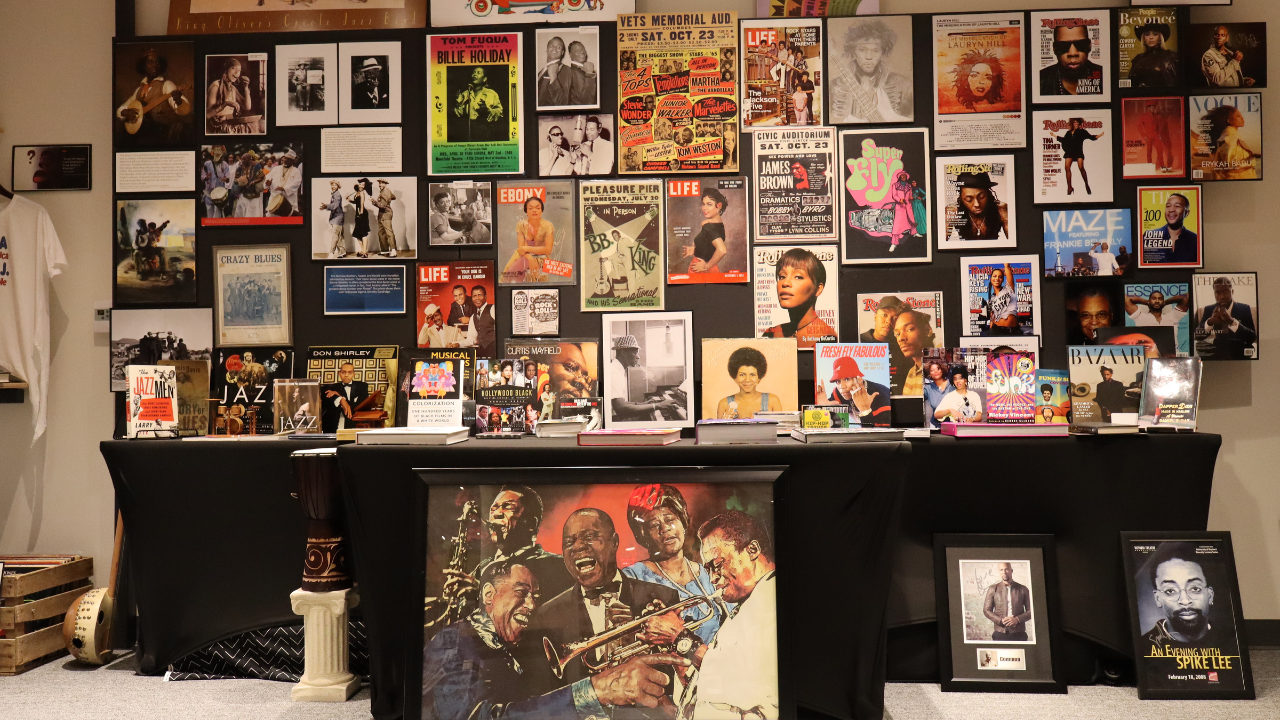

When students step into Room 324, Building 11, at Sinclair, the space almost tells who it belongs to before anyone speaks. The walls carry eclectic assortments of photographs, letters, quilts and memorabilia. All objects donated by Michael Carter and his wife, each piece part of a living story. This is “Our American Journey”, Mr. Carter’s vision brought into being.

Carter’s love of history runs deep. He studied it in college, taught it in middle and high school and over the years amassed a collection of artifacts quietly in his life.

That collection found opportunity when Dr. Khalid El-Hakim brought a traveling hip-hop exhibit to Sinclair in early 2020. Carter watched that exhibit and thought of how he would love to do something similar; during the COVID-19 pause, he refined his idea.

at the Our American Journey classroom. MALIYA AYAMBRIE

He first set up in the college library’s loggia, a small glass-walled room near the marketplace as a one-month trial.

He admitted he had “kept his fingers crossed” that it would last longer. When Dr. Johnson and Dr. Scott Marklin saw the display, they encouraged permanence. That temporary setup remained there for three and a half years until the collection moved into its current, more capacious home.

Every artifact in the room was donated by Carter and his wife. But the exhibit is not just a display, it is a space built to provoke thought, grief, memory and conversation. Carter is clear about why he does it:

“African-American history is American history … there are so many untold stories because people have either been reluctant or haven’t wanted that story to be told,” Carter said.

He rejects narrow historical narratives, the ones that stop at the Civil Rights era, Martin Luther King, Rosa Parks. He argues that so many rich stories are omitted. “Our American Journey” seeks to give them presence and force.

Visitors walk through themed zones: Early slavery, emancipation, Jim Crow, migration, wartime service, civil rights, sports and more.

Among the striking items is a KKK robe and hood, quilts honoring Negro League teams and framed portraits and documents of lesser-known figures.

and memorabilia, donated to the Our American Journey

classroom. MALIYA AYAMBIRE

In a 2021 “Dayton Daily News” piece, Mr. Carter described some included objects: quilts by Kettering’s Carroll Schleppi, Negro Leagues references, and memorabilia calling attention to overlooked chapters.

Carter hopes visitors feel something unsettled, inspired and provoked. He has already seen it: People moved to tears and experiencing things they had previously not known. He plans to install a response wall for visitors to leave questions, impressions or reflections.

To Carter, the gallery is also therapeutic. He likens it to testimony in a Black church worship and not a space of sorrow but a space of witnessing:

“Spaces like this … is our testimony that we have overcome … it’s not a space of sadness … We’re standing on the shoulders of those folks,” Carter said.

and memorabilia, donated to the Our American Journey

classroom. MALIYA AYAMBIRE

He opens the room to community purposes. Faculty, student groups and organizations are welcome to reserve time; he collaborates widely with the African-American Male Initiative, ACES, NSBE and LGBTQ+ groups to ensure the space is alive and shared. The exhibit’s motto, “Remember, Reflect, and React” stems from that intent.

Ambitions go beyond the walls. Carter leads weekend field trips like Detroit’s African American History Museum, Motown studios and Cleveland’s Rock & Roll Hall of Fame.

These excursions root what is inside the gallery in real-world places. He also desires to bridge continents particularly Ghana and Senegal. He spoke in tears of Gorée Island, also known as the “door of no return” in the slave trade.

“It’s the last thing Africans experienced on the coast … before being shipped to America,” Carter said.

and memorabilia, donated to the Our American Journey

classroom. MALIYA AYAMBIRE

Though the scope and the history of “Our American Journey” is layered and multi-faceted, Carter summarizes it as something fundamental to who he is.

“It’s a passion project. Everything in there … comes from the heart and what we believe in,” Cater said. “It’s important for African Americans to learn who they are. And it’s important for all Americans to know African-American and Black contributions to this country.”

This classroom is more than a museum. It is a gift, a collection made public, a space of memory, confrontation and possibility. Carter has built something that gave his private archive a home of public meaning. Anyone who walks in is invited to pause, question, feel and carry history forward.

Maliya Ayambire, staff writer

Checkout more posts by the Clarion:

- Sinclair prepares for the 8th annual Faith Fair

- Tartan Spotlight: Professor Paul Hansford brings decades of industry experience to the classroom

- PHOTOS: The International Peace Museum opens ‘Season For Non Violence’

- YourVoice: Students raise concern over possible ICE operation in Springfield

- PHOTOS: Dayton Bloody Mary Showdown celebrates a favorite cocktail

- Sinclair to hold Feed the Birds events