They say that history should be remembered, not repeated. No place is that truer than on Wright-

Patterson Air Force Base, where a landmark peace agreement was forged after a month of

intense negotiations to bring an end to the Bosnian War. In the lead up to the 27th anniversary of

the Dayton Accords, there was no better place to go than the rooms where it all happened.

To most of us, 1995 was a year among many. Coolio and TLC were competing for dominance of

the Billboard Hot 100, while a little movie called “Batman Forever” shifted the cultural zeitgeist.

But on the news and in cities across the Balkans, a brutal conflict was raging where ethnic

cleansing and other war crimes were deployed against innocent civilians. The Bosnian War saw

sieges the likes of which the world had not seen since the end of the Second World War and

crimes against humanity that were a shock to those that heard about them. Even now, years later,

the names Srebrenica and Mostar bring to mind the horrors of the conflict.

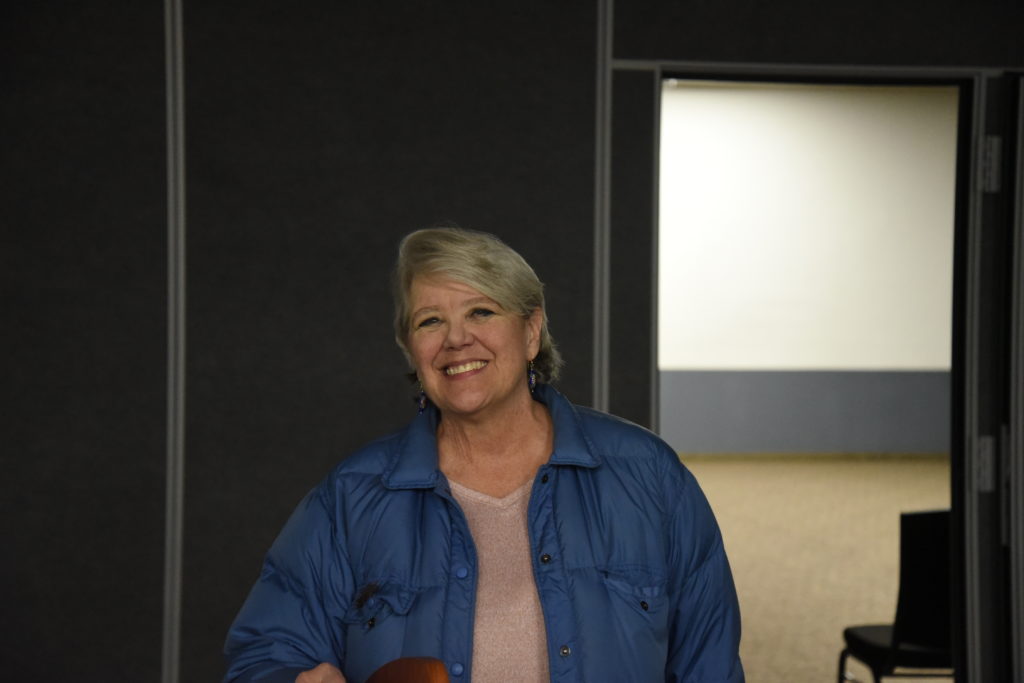

For Janelle Bailey, then 20 years-old, the year was just like any other. A housekeeper at the Hope

Hotel at the time, she had no idea that soon, the world would come to Dayton with all eyes

shifting to her hotel and the base it was on.

“We had eight days notice,” she said. “I’m sure others on base had a more advance warning than

the rest of us, but that took awhile to filter down to the staff and when it did, we had just eight

days to get ready.”

Not unlike many youths at the time, Bailey was focused on her job and family, not sparing the

news too much time. She is now a manager at the hotel, the years giving a deeper appreciation

for what happened that winter, 27 years ago.

“Back then I was in my early twenties and remember thinking it was just a pain when it all

started. We had to get wanded everyday, needed special passes, and a fence was even put up

around the area the dignitaries would be.”

“It was intense and I was just twenty years old. The importance of it did not hit me, however,

until I saw the presidents walking together. I realized that what was happening was very

important and it made me watch the news. I found out I was a part of history, part of changing

the world and it was pretty humbling. I stopped all my complaining then,” she said.

Little has changed in the intervening years, I notice as she takes me around the Richard C.

Holbrooke Conference Center, named for the US Ambassador to the UN credited with making

the talks a reality. The rooms where the initialing of the agreement took place before the press,

where maps were consulted, and where meetings between dignitaries took place are as pristine

now as they were then. As we walked around, it is easy to feel the weight of history hanging over

the building.

By the time the talks in Dayton were held, the war in Bosnia and Hercegovina had raged since 1992. The European Union’s efforts to make a deal between Bosnian leader Alija Izetbegovic,

Croatian President Franjo Tudjman, and Yugoslav President Slobodan Milosevic had repeatedly

floundered. A US-led effort to try to bring peace to the Balkans spearheaded the search for the

perfect place those talks could take place. Surprising many, Dayton was chosen.

“When former Ambassador Patrick Kennedy heard about the visiting officer’s quarters and how

they were all the same, he thought Dayton would be the perfect place. They wanted the leaders

sequestered so they could focus on making an agreement and for them to be away from the

media to prevent any grandstanding in public,” said Dr. Mary Ramey, Project Coordinator at the

Dayton Peace Museum.

She joined us that evening, offering further insight from her wealth of knowledge about the talks

and their importance.

“It was important that there were no differences in the accommodations. No one was put above

the other. They really wanted them to feel that they were all equal and so special attention was

paid to ensure that each room had exactly what the other rooms had,” Dr. Ramey added.

“The rooms were renovated and then we had eight days to fine tune everything,” Bailey said.

“I’ve heard it said that the paint was still drying when the dignitaries came and that is absolutely

true.”

“The day the delegations arrived you could feel the intensity, the worry, the concern,” said

Bailey. “We kept hoping that everything would be ok and that the rooms would be fine. After

everyone got into their rooms we didn’t hear anything. The next day there were zero complaints

about the rooms. As housekeepers, that was really what we focused on and we just went about

our work as best we could.”

Related article: Sinclair history teacher artwork on display at the Dayton Peace Museum

For Daytonians, what followed was a month of not really knowing whether an agreement would,

or could be reached. News came out in snippets. Inside Wright-Patterson, furious negotiations

went down to the wire.

“Talk about snatching victory from the jaws of defeat,” Dr. Ramey said. “It got to the point

where, near the end, Holbrooke was telling his staff goodbye. Then Milosevic conceded a point.

Holbrooke then took it to the Bosnian leader and at first Izetbegovic did not respond. So he

repeated himself and finally Izetbegovic said, ‘It is not a just peace. But my people need peace.”’

Bailey remembers how fearful staff were that a deal would not be made.

“There was talk that maybe they would need to cancel our thanksgiving vacations.”

But a deal was indeed made, one that continues to this very day. It is a saga that locals followed

closely.

“The people of Dayton really took this to heart and wanted the talks to succeed. There were

peaceful demonstrations and our founder, Chris Dull, even played the Adagio in G minor that the

cellist of Sarajevo Vedran Smailovic performed during the siege to encourage the delegates.

People even put candles in their windows,” Dr. Ramey said.

Steel doors can still be seen in the conference center. The buildings that housed the delegations

remain. Even the presidential suites look much the same sans a wall. At first glance, there is little

sign that once, hundreds of delegates descended on this part of Wright-Patterson Air Force Base

to end a war that had by then destroyed millions of lives. But right next to where the Bosnian

leader was housed, the Peace Walk remains. It is a concrete sidewalk that once linked the

conference center to where the delegations were housed. Today, visitors can still walk part of it

just like the Balkan leaders did inbetween talks.

Thanks to Bailey, artefacts from the event can be seen on display in the Dayton Peace Musuem.

They include a map used by delegates and Croatian leader’s plaque among other items.

“When it ended, it was just rip and strip. Everything was gone. I knew these things meant

something, that they should be preserved so I asked if anyone wanted them and when I was given

the clear I took them home,” she said.

Accompanied by Ramey and Bailey on the short stroll it takes to reach the end of the sidewalk, I

am reminded of just how much can be achieved when people come together no matter their

differences. The Dayton Accords are proof of that.

“I think for most people, it happened, it was in the news, and it’s a part of history,” said Bailey,

“But going to the peace museum and speaking to you has made me realize that I was a part of

something massively important. I was there. It makes me so proud of the work we did.”

Ismael Mujahid

Reporter