Thanksgiving might feel like a cozy, predictable holiday with turkey on the table, parade on the TV and someone arguing about football, but its history is anything but simple. Behind the classic American imagery lies a surprising mix of myths, culture clashes, political maneuvering and centuries of reinvention. Which makes the whole thing a lot more interesting.

The usual story starts in 1621, but the version many of us grew up with has been heavily airbrushed. Yes, the Pilgrims in Plymouth held a harvest celebration with the Wampanoag people. Yes, there was food and goodwill. But the whole scene looked very different from the picture-book version.

For starters, nobody sat down to a perfectly roasted turkey with stuffing and cranberry sauce. They ate what they had: wild fowl (maybe turkey, but also maybe ducks or geese), venison brought by the Wampanoag, dishes made from corn and squash and likely some seafood. No pies, no mashed potatoes and definitely no marshmallow-topped yams.

Many of the ingredients did not even exist in New England yet. Instead of a neatly scheduled afternoon meal, the event lasted three days. Imagine your relatives staying for a whole weekend instead of one dinner… terrifying.

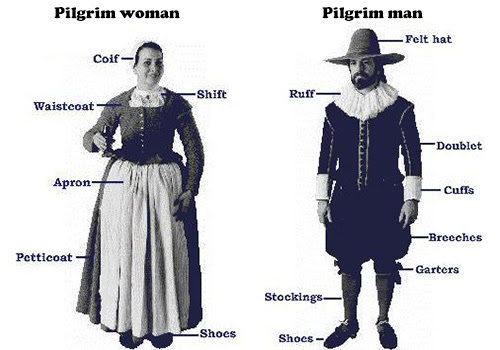

Also, those famous Pilgrim black outfits with shiny buckles are unfortunately pure fiction. Their clothing would have looked downright drab compared to the costume-section version. The only thing they definitely had in abundance was relief. After a brutal first winter, just being alive and able to harvest anything at all was worth celebrating.

But here is the twist: That 1621 feast was not considered a “Thanksgiving” at the time. Colonists used that word for solemn, prayer-heavy days dedicated to thanking God for something specific like rain or a military victory. The big feast with the Wampanoag did not fit the definition at all. It was simply a harvest celebration. The whole “First Thanksgiving” branding came centuries later.

The holiday we now recognize was actually shaped by one incredibly determined woman: Sarah Josepha Hale. She was a 19th-century magazine editor who believed the country needed an official holiday rooted in gratitude, unity and food.

She spent decades writing letters, publishing recipes and pushing for a national Thanksgiving. Hale’s vision already included turkey, stuffing, pumpkin pie and the warm family vibe we now associate with the day.

Her campaign finally worked. In 1863, in the middle of the Civil War, President Abraham Lincoln declared a national Thanksgiving Day in an effort to bring the fractured nation together. From that point on, the holiday became annual but it still did not look exactly like what we celebrate now.

Immigrant communities across the country added their own culinary traditions: Italian families brought pasta dishes, German families added sausages and breads, African American cooks in the South gave the day some of its most beloved staples like sweet potato pie, mac and cheese, collard greens and cornbread dressing. The holiday turned into a giant melting pot, literally and figuratively.

The 20th century layered on even more traditions. Macy’s launched the now iconic Macy’s Thanksgiving Day parade in 1924, originally featuring zoo animals instead of giant balloons.

Football, which had been part of Thanksgiving since the late 1800s grew into an all-day spectacle thanks to the NFL. Norman Rockwell’s iconic “Freedom from Want” painting in the 1940s cemented the image of grandma presenting the turkey to a beaming family. In 1941, Congress officially locked Thanksgiving onto the fourth Thursday in November, sealing our fate as participants in the busiest travel week of the year.

While Americans tend to treat Thanksgiving as uniquely a U.S. celebration, almost every culture has some kind of harvest celebration or gratitude festival. Canada has its own Thanksgiving in October. China celebrates the Mid-Autumn Festival with mooncakes and lanterns. Korea’s Chuseok, India’s Pongal and Germany’s Erntedankfest all revolve around giving thanks for abundance and community. It turns out humans everywhere appreciate a reason to enjoy a feast with good company.

The history of Thanksgiving is not a straight line. It is a messy, evolving and culture-blending story. Maybe that is the real charm of it. Every year as new dishes appear on tables and new traditions take shape, the holiday continues to change. Thanksgiving has never been stuck in 1621. It grows with us, one plate at a time.

Maliya Ayambire, reporter

Checkout more posts by the Clarion:

- 5 ways to start spring semester off right

- National Park Service drops MLK Day and Juneteenth, adds Trump’s birthday

- Art for everyone: Open studio session at The Contemporary Dayton

- A look back at ‘Star Wars: The Force Awakens’ 10 years later

- Weary of winter? Here’s 5 tricks to beat the blues

- More than 10% of incarcerated students could lose access to higher education under HB 338