There are many famous individuals who come from the city of Dayton, such as Orville and Wilbur Wright, two brothers who caused Dayton to be known as, “The Birthplace of Aviation.” There are also individuals who were a part of the entertainment industry such as Roger Troutman, who spearheaded the funk movement and as a result, influenced West Coast Hip-Hop. Additionally, there are multiple inventors who created things that we continue using in our day to day life, such as the cash register.

Among these countless remarkable people is Paul Laurence Dunbar, an early African American novelist, poet, and playwright. Although having died at 33 years old of tuberculous in 1906, Dunbar left quite an impact in his short lived life.

For instance, Dunbar was the first African American writer of any sort to achieve great acceptance from white audiences. Due to this acceptance, he achieved national acclaim.

The house in which he formerly lived in continues to stand in perfect condition. Purchased by the state of Ohio in 1936, the Paul Laurence Dunbar House is unique for being the first state memorial honoring an African American. Previously, it stood on a location called North Summit Street, now it has been renamed as Paul Laurence Dunbar Street in his honor.

When asked how many people enter the site, Gregg Smith, a tour guide at The Paul Laurence Dunbar House replied: “We average around 4,000 to 5,000 a year.”

While Dunbar was indeed born in Dayton, this house was simply one he spent his final years in. Dunbar actually purchased the two-story brick home for his mother, Matilda Dunbar.

Matilda was born into slavery in the state of Kentucky, relocating to Dayton in 1866. She ultimately met Joshua Dunbar and their marriage would produce two children who consisted of Dunbar himself and a girl named Elizabeth who would, unfortunately, die before her third birthday. Similarly, Joshua would die when Dunbar was thirteen.

A variety of sources centered on Matilda highlight how a strong bond existed between her and her son. A photograph even exists of the two sitting side by side, upright and proper. In regards to The Paul Laurence Dunbar House, Dayton history reveals that its location was far different than how it is in the present.

Very few people of African American descent resided on what was formerly North Summit Street. At that particular time, the mass majority of residents were described as being of Russian and Hungarian ethnicity. The fact Dunbar bought his mother a home in such a community, as well as he died under her roof, brings the strong impression that there existed a powerful bond between the mother and son.

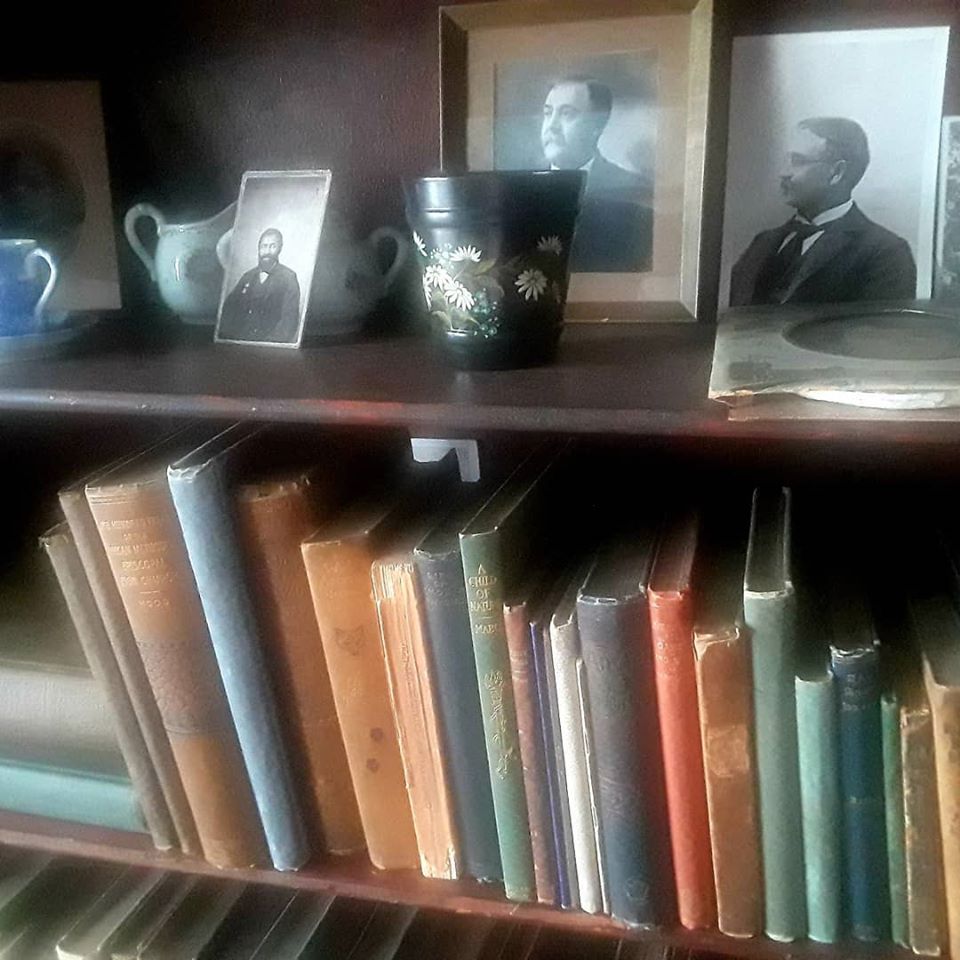

Other than receiving the opportunity to learn about Dunbar in vast detail while touring the home, people are essentially time traveling: walking through a building untouched by time.

Gazing over wallpaper that was popular from its era, walking into rooms where family members are displayed in black and white photographs, and seeing the typewriter where he corresponded with others. To see such artifacts from that era, one cannot help but recall how differently life was lived in the 1900s.

Throughout America, the African American community also held Dunbar’s creations in high regard, even decades after he died. For instance, in 1969 the renowned poet Maya Angelou would name her famed autobiography, “I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings” after Dunbar’s poem, “Sympathy.”

Admittedly, in terms of the present-day mainstream media, the chances of hearing Dunbar getting mentioned in a film are slim, in contrast to bygone creatives such as Langston Hughes or James Baldwin.

While a lover of poetry, Professor Furaha Henry-Jones of the English department was unfamiliar with Dunbar’s work until adulthood. Until that point, she had never heard of his name while in school. She holds awareness of how Dunbar was once a household name in the country – as well as how Hughes deemed Dunbar and Walt Whitman his biggest influences, which further caused her surprise as he was seldom spoken of during her schooling.

Still, Henry-Jones would find his work to be insightful. What she greatly appreciated the most about his work was how varied it had been.

“He had poetry, short stories, novels, vignettes – journalism,” Henry-Jones said, listing off the multiple creations. “He wrote a variety of editorials.”

In regards to Dunbar’s journalism, Henry-Jones is referring to the “Dayton Tattler,” which was published by none other than Orville Wright while composed and edited by Dunbar. Only three issues were stated to have existed, but the paper itself is historic for being Dayton’s first African American newspaper.

“What impressed me the most about him was that in such a short life, he was able to do so many things,” Henry-Jones continued.

Ultimately, Henry-Jones feels he is not dismissed or ignored by young Daytonians with creative minds.

“Young black writers, that I know, his life and his work definitely is something that they look up to and that they respect,” Henry-Jones explained. “I know there are some who have written works in honor of Dunbar. I would like to see more attention to his life and his legacy through writing among all writers.”

For those who love poetry, history or have an interest in The Paul Laurence Dunbar House, it is free to the public, open Friday to Sat. from 10 a.m. to 4 p.m.

Ayzha Middlebrooks

Associate Editor