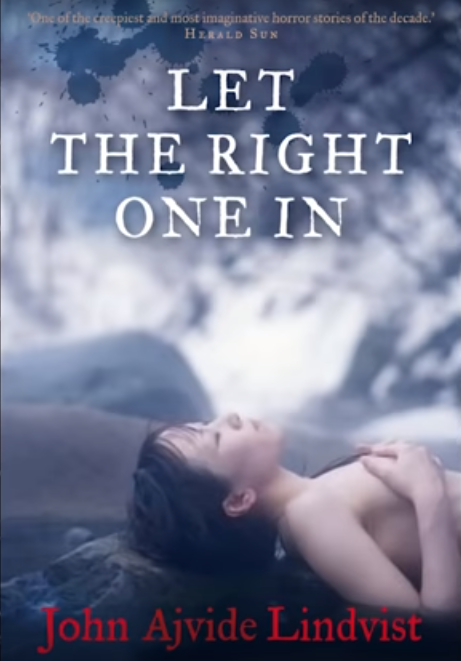

When John Ajvide Lindqvist’s novel “Låt den rätte komma in” was published back in 2004, it was his debut novel. A few short years later, he was referred to as the “Swedish Stephen King,” according to the New York Post, despite it being his only truly famous novel.

The novel in question took its name from a Morrissey song: “Let the Right One Slip In,” and it, in many ways, rewrote one of the oldest horror stories in the cannon of the genre.

It was a re-imaging of the vampire myth that stressed realism, and took on deep, devastating subjects such as existential anxiety, social isolation, divorce, pedophilia and murder. The book is a harrowing read, not just for the terror therein, but for the layers it provided to horror. It became a horror of emotional honesty and pain.

The book obviously spawned a movie. Well, two to be exact. So, I’d like to talk about them both, because, for me, they are two of the saddest horror movies ever created.

My initial experience with the films was through an article that had listed the original, Swedish version, “Let the Right One In,” as one of the best horror movies of the early aughts. Obviously, as a horror fan I was intrigued.

But it was a Swedish movie, there was no way I’d be able to find it at a video store around here. So, I put it on my Netflix DVD queue and promptly forgot about it.

It wasn’t until trailers for the remake had started showing in late summer 2010 that I’d even thought of it again. But, it was an American remake of a critically acclaimed foreign language film. Surely it was gonna be crap, right?

I showed up to the theater on opening weekend, being that I basically saw and still see a movie every weekend, and found it to be the most interesting option. It was directed by Matt Reeves, the guy who has since transformed the new Planet of the Apes films into a series worthy of its predecessors clout. Though, at that time, he was just the guy who had directed “Cloverfield,” a pretty forgettable, but halfway decent kaiju movie.

In other words, I wasn’t expecting much. But, once the film had ended, it quickly became my favorite film of 2010. Beyond that, I connected with it on a level I hadn’t connected with since, well, E.T.?

Which is to say, it struck some sort of primordial chord in me that cut deep down into a childhood trauma that has affected and infected all of my tastes and appreciation for films about lonely, sad kids dealing with the trauma of early-onset-existentialism.

Related Article:

In other words: I connected with it because it was a movie about children dealing with things that they were too young or too innocent to fully grasp. Which, is, I feel, kind of untrue, obviously. I’ve always felt that kids were very capable of handling intense, heady themes. Many of the greatest children’s stories are filled with themes on death, identity, and anything else you might find in material typically created for adults.

In fact, if we take into account the original Grimm’s Fairy Tales, in their original incarnations, we’d find that many of the stories designed for children were filled with heady, dark material–things that would certainly be deemed and have been deemed as such by the great children’s media emperor, Disney, as inappropriate or too cerebral for children.

“Let Me In” and the original Swedish film “Let the Right One In” are no different. They would fit alongside Hansel and Gretel’s tale of cannibalism and child abuse or the self-mutilation and baby-napping of “Rumpelstiltskin.”

It is a story about a young boy, with psychotic tendencies, who in both versions, wears a mask and brandishes a knife, revealing serial killer aspirations. As for Eli (pronounced as Elli, though the name is changed to Abby in the American version) she is a vampire, forced forever to exist as a young child, given an adrogynous name because, in actuality, Eli is a boy.

The movies, much like the book, explore many of the same themes, though the Swedish version pulls fewer punches. Through Eli (or Abby) and Oskar (or Owen’s) interactions we are shown from the inside what it might feel like to feel and desire things that are socially unacceptable or morally wrong; Oskar’s alienation and sadness over the bullies who haunt him daily at school driving him towards violence, and Eli’s thirst for blood, something that, as a vampire she requires to live.

And that is where, I think, the story is its most powerful. It takes a myth that is centuries old, has been written about to the point of mind-numbing ubiquity, and turns it slightly towards a new direction.

Whereas the horror of most vampire stories is the fear of becoming the monster, Eli has no desire, other than in one instance, to turn those that she cares about into the monster that she fights against. So then, what if we are already monsters?

With Oksar, as already mentioned, it is explicitly stated in both versions that he has murderous tendencies and desires. But Eli’s adult companion, Håkan (Thomas in the American version, played brilliantly by a pathetically empathetic Richard Jenkins) has pedophilic tendencies, something that is highlighted to a greater degree in the book and merely suggested in the movies.

The films explore then, through the vampire mythos, the nature of evil and the internal struggle to be morally good, despite that which might pull from inside you.

Oskar with his murderous tendencies and Håkan, with his pedophillic tendencies fight against their own inner evil, much in the same way that Eli does. It should be noted that Håkan actually kills people and drains their blood so that Eli might drink it to survive.

He does this not because he enjoys it, but because he truly loves and cares about Eli. In both versions and in the book it is revealed that Eli knew Håkan as a child, and it goes then to infer that what has happened to Håkan will inevitably happen to Oskar.

I don’t want to give too much away, and although the American chooses to place the major event that I’m avoiding here at the beginning of the film, I still won’t reveal it because I think it’s important enough to the plot.

I will however say that it is one of the strangely sweet parts of the film, a moment of sacrifice on the verge of doom that hammers home the emotional turmoil inherent in the evil within people.

In other words, these characters know that what they’re doing is wrong and they know that they cause pain and have caused, in the case at hand, excruciating pain to other people. But, they are trying to be decent, in the only way they can.

Throughout the film, Oskar and Eli communicate through their shared apartment wall via morse code. By the film’s end, Oskar sits on a train headed for a place the audience never finds out, a large chest sitting beside him.

Then, form inside the box, comes a series of knocks. Oskar waits a second, smiles at the box and knocks back. We know that nothing good will happen, nothing good has happened thus far, but they are bonded by their mutual inner struggle. It’s sweet in a sort of painful way. The kind of sweet that exists in the secret places of our mind where we hide our hidden dreams and wishes, in the hope that exists in young love, before time dashes out its flame.

Well then, now that you’re properly sad, I’ll end it. Next week we’ll discuss a movie that just recently came to theaters. It is arguably NOT a horror movie, by traditional standards, but it’ll definitely fall into that category on streaming services (and video stores, if they still exist somewhere). It’s a “horror” movie that’s been released in the middle of summer.

Richard Foltz

Managing Editor